Imi Lichtenfeld & Krav Maga

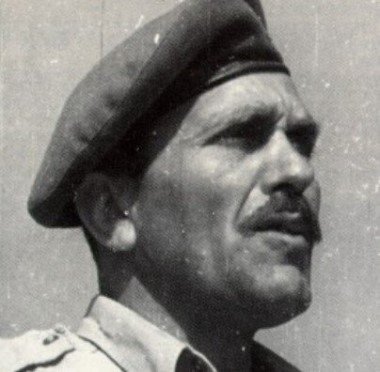

Imi Lichtenfeld (later known in Israel by his Hebrew name as Imi Sde-Or) was born in 1910 and grew up in Bratislava (then part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire),

where his father, Samuel, ran a gym and served as a police officer and self-defense instructor. Imi’s daily life involved lifting weights, gymnastics, wrestling,

and boxing, and he proved gifted across them all. As a teenager and young man, he competed in wrestling and boxing at high levels, winning national and regional titles,

but just as important, he absorbed his father’s practical approach to violence management: avoid trouble if you can, finish it quickly if you can’t, and teach in a way

ordinary people can actually learn. Lessons, which he put into practice when developing Krav Maga.

Imi Lichtenfeld (later known in Israel by his Hebrew name as Imi Sde-Or) was born in 1910 and grew up in Bratislava (then part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire),

where his father, Samuel, ran a gym and served as a police officer and self-defense instructor. Imi’s daily life involved lifting weights, gymnastics, wrestling,

and boxing, and he proved gifted across them all. As a teenager and young man, he competed in wrestling and boxing at high levels, winning national and regional titles,

but just as important, he absorbed his father’s practical approach to violence management: avoid trouble if you can, finish it quickly if you can’t, and teach in a way

ordinary people can actually learn. Lessons, which he put into practice when developing Krav Maga.

The late 1930s in Bratislava saw violent street clashes fueled by rising fascism that spilled into and targeted Jewish neighborhoods. Imi led groups of young Jews who protected shops, markets and public gatherings from these organized assaults. Those confrontations shaped his thinking. Boxing footwork and wrestling control worked, but only after they were adapted to crowds, uneven footing, multiple assailants, and the shock of surprise – it was by recognizing that even trained fighters/martial artists reacted naturally and instinctively when caught unaware, that he made this part of the Krav Maga system; not what you might want to do when attacked, but what you will do. He learnt to prioritize simple movements, aggressive counterattacks, and the constant search for an exit, as part of his self-defense training. Out of necessity rather than theory, he began to assemble these ideas together that would later become the foundation(s) of Krav Maga.

As war closed in, Imi left Europe in a hazardous migration that took him across the Mediterranean and eventually to British-controlled Palestine. There he found a soci

was asked to codify close-quarters methods for people with little time and varied backgrounds. The emphasis stayed pragmatic: natural reactions harnessed into simple

defenses, simultaneous counterattacks rather than elaborate sequences, and constant movement toward safety. When the State of Israel was established in 1948, Imi became

the chief instructor for physical training and hand-to-hand combat at the Israel Defense Forces’ school of combat fitness. Over roughly a decade and a half of service he,

along with others, refined a curriculum that could scale to conscripts and special units alike; short, teachable progressions, pressure-tested drills, and clear priorities

for gun, knife, and stick threats.

As war closed in, Imi left Europe in a hazardous migration that took him across the Mediterranean and eventually to British-controlled Palestine. There he found a soci

was asked to codify close-quarters methods for people with little time and varied backgrounds. The emphasis stayed pragmatic: natural reactions harnessed into simple

defenses, simultaneous counterattacks rather than elaborate sequences, and constant movement toward safety. When the State of Israel was established in 1948, Imi became

the chief instructor for physical training and hand-to-hand combat at the Israel Defense Forces’ school of combat fitness. Over roughly a decade and a half of service he,

along with others, refined a curriculum that could scale to conscripts and special units alike; short, teachable progressions, pressure-tested drills, and clear priorities

for gun, knife, and stick threats.

After leaving the army in the late 1960s, Imi settled in Netanya and turned to civilians, law enforcement, and security professionals. He translated the military core into age- and context-appropriate programs e.g., what a schoolteacher needed at a bus stop was not the same as what a police officer needed when serving a warrant. The system/approach should help ordinary people go about their lives with less fear, teaching avoidance, situational awareness and de-escalation first, whilst reserving decisive violence for situations where there was no other option. In 1978 he helped form the Israeli Krav Maga Association to formalize teaching standards, grading, and instructor preparation. Under his guidance a first generation of senior instructors emerged and began to spread the method beyond Israel, taking it to Europe and the Americas and adapting drills to new cultures and legal environments.

Imi’s teaching style was direct and unpretentious. He insisted that techniques be grounded in body mechanics anyone could reproduce under stress: redirect the line of attack

rather than wrestle for the weapon, strike vulnerable targets to create time, keep your balance while breaking the attackers, and scan for the next problem. He discouraged

choreography and encouraged feedback loops—if a solution was difficult to remember, required fine motor precision, or collapsed under pressure, it didn’t belong. He valued

scenario training and incremental stress, but he also valued safety, building contact and complexity in stages so students could train hard for years rather than flame out

in a month. Many who trained with him recall the combination of gentleness and rigor: a grandfatherly patience married to a demand that every movement have purpose.

Imi’s teaching style was direct and unpretentious. He insisted that techniques be grounded in body mechanics anyone could reproduce under stress: redirect the line of attack

rather than wrestle for the weapon, strike vulnerable targets to create time, keep your balance while breaking the attackers, and scan for the next problem. He discouraged

choreography and encouraged feedback loops—if a solution was difficult to remember, required fine motor precision, or collapsed under pressure, it didn’t belong. He valued

scenario training and incremental stress, but he also valued safety, building contact and complexity in stages so students could train hard for years rather than flame out

in a month. Many who trained with him recall the combination of gentleness and rigor: a grandfatherly patience married to a demand that every movement have purpose.

Krav Maga’s later growth brought organizational forks and new federations, but Imi remained the touchstone. He continued to demonstrate, correct, and examine black belts well into his later years, updating material as real incidents and student feedback accumulated. The system’s expansion into police and military units abroad brought new problems—handcuffing transitions, team tactics, use-of-force policy—and he encouraged specialists to develop modules while keeping the core simple enough for civilians. By the 1990s, his approach had become one of the world’s most recognizable modern self-defense methods, distinct for its practical tone and its insistence on integrating awareness, legal context, and post-incident actions with the physical curriculum.

Imi Lichtenfeld died in 1998 in Netanya, leaving behind a living system rather than a closed canon. His legacy is not a library of elaborate techniques but a set of concepts and priorities that continue to guide instructors: prevent when you can, act decisively when you must, and design training that works for stressed, surprised human beings in ordinary clothes. The path from a Bratislava boxing ring to IDF training grounds to gyms around the world is unusual, but the thread is easy to trace. Faced with real problems, Imi built solutions that ordinary people could remember and use. That, more than any single technique, is why his work/Krav Maga endures.

If you are interested in learning more about the history and development of Krav Maga and how it fits into the landscape of Israeli Martial Arts, click here. You can also learn more about Krav Maga Yashir by clicking here.